Supply chain - Part 1

Who Should See What?

Tracking Distribution Through Data:

Today’s tracking tools can produce a lot of data, but the challenge is to provide the right data to users and to regulatory bodies.

Most food safety management and ERP systems provide at least a one-step-forward, one-step-backward functionality when it comes to tracking and tracing products in the supply chain. The FDA and other government regulators would like to see more info available at any step along the supply chain. But does that mean that all participants need access to all the data? In this article, we look at the issues involved in tracking products through the supply chain and who should have access to the data.

Roadblocks to Data Access Along the Supply Chain

Tracking and tracing food products and ingredients through the supply chain has been a perennial problem—often due to many reasons, as Bryan Cohn, SafetyChain Software senior solutions engineer, points out. “Predominantly, it has been issues with older, siloed legacy systems and the lack of data normalization within company operations and the industry as a whole.”

The importance of a single database is a recurring theme. “Over the years we have talked about the requirement of ERP systems to integrate data from best-of-breed solutions, which is something that some ERP providers are better at than others,” says Maggie Slowik, IFS global industry director for manufacturing. She contends that an ERP system should combine multiple critical capabilities and maintain a continuous data thread (in a way a “digital product passport”) that tells the unique journey a specific product has undergone. This continuous data thread speeds up the retrieval of batch information, as required by FDA and/or other regulators.

Make your own healthy salad, but do you know where all the ingredients came from? Chances are each ingredient has its own story to tell—but what if one of them is contaminated with a pathogen? FDA hopes to make each ingredient’s origin traceable quickly via modern technology. Image courtesy of Silvia from Pixabay

by Wayne Labs, Senior Contributing Technical Editor

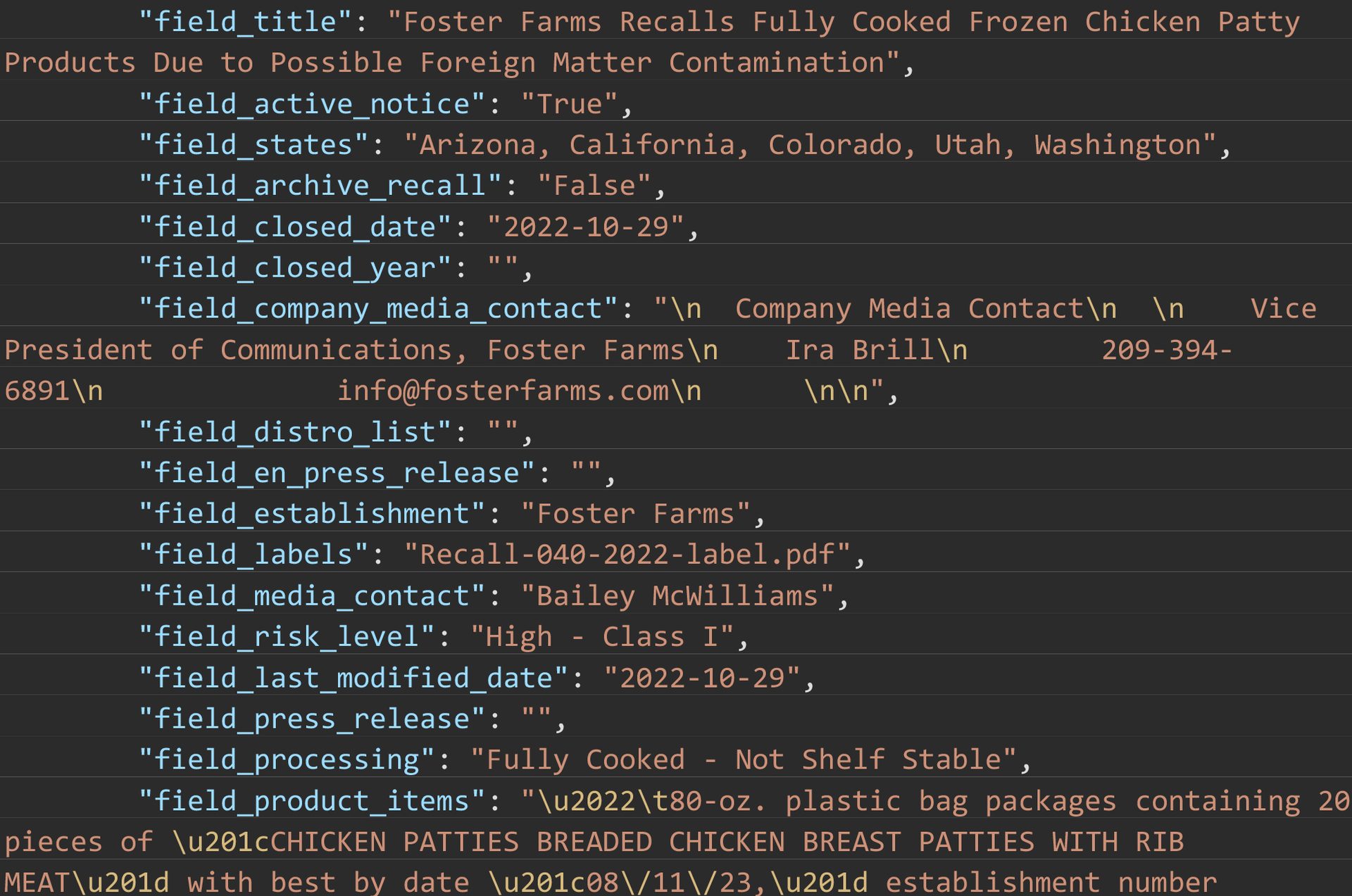

This is a sample text output of USDA/FSIS’s Recall Alert API showing the cleaned-up contents of a JSON file with database records and their fields. Programmers can use this data to build an output graphic or chart that matches the needs of their clients. In addition, the code can be written such that if a recall affects a given ingredient used in a processor’s product, they will get an immediate indication of the problem ingredient. Image courtesy of FSIS

Getting everyone on board in the supply chain from farm to retailer has been a longstanding problem. “Adoption is still quite slow and primarily initiated by grocery retailers or relatively small-scale implementations aimed at paying a fair price to the growers, for instance, cacao and coffee,” says Marcel Koks, Infor industry & solution strategy director for food & beverage. “In many cases the value is not that obvious for upstream suppliers and farmers. Big drivers for adoption of multi-enterprise track and trace and transparency will be compliance with regulations such as FSMA 204 (establishes a foundation for end-to-end traceability in the U.S.) and the Digital Product Passport in the European Union.”

Francine L. Shaw, cofounder of My Trusted Source and author of a new food safety book entitled Who Watches the Kitchen, points out other roadblocks and hurdles preventing widespread supply chain tracking:

• Lack of standardized systems and processes across different countries and regions can make it difficult to track products. Different countries may have different regulations, reporting requirements and data formats, making it challenging to integrate data from different sources.

• Many food manufacturers do not have real-time visibility into their supply chain operations. This lack of visibility can also make it challenging to coordinate with suppliers and retailers in different regions.

• Data silos—different systems and databases make access and integration difficult.

• Communication and language barriers plus different time zones and cultural norms can lead to miscommunication, delays and errors, which can disrupt the smooth flow of the supply chain.

• Cost constraints are a challenge in implementing technology solutions, especially for smaller manufacturers and farms.

• Companies may be hesitant to share sensitive information about their supply chain with external partners due to data security concerns, cyberattacks and data privacy.

• Lack of collaboration and partnership: Food manufacturers may be hesitant to share information and collaborate with competitors or suppliers for fear of losing a competitive advantage.

The last two bullet points are certainly valid reasons for supply chain participants to think that “one-step backward, one-step forward” is good enough. “I believe that the one-step approach is actually the best foundation to build from,” says Steven Burton, founder & CEO of Icicle Technologies Inc. “It’s precise, achievable—and clear focus is very practical from both a technical and business perspective.”

“What we’re lacking most is a mechanism to capture only the portion of the traceability chain, only when we need it,” adds Burton. “This is the only means by which, in my opinion, we’ll ever be able to move across every step of a supply chain. Everyone in the supply chain should be required to maintain their supply chain information in a standard format and expose it using a standardized application programming interface (API) available to regulators—and only regulators—on demand.”

“But the regulatory bodies are different, the frameworks they use aren’t necessarily cohesive, and if you manufacture or sell products across any borders the whole process gets a lot more complicated,” says Burton. “The harmonization efforts from organizations like the Global Food Safety Initiative have been a really good start. Also, it will be very interesting to follow the roll-out of the new FSMA traceability rule to see how the requirements are implemented and which countries will follow the FDA’s approach.”

Burton’s company is currently developing an API connector to the FDA recall alerts system, called Recall Enterprise System (RES), which will pull that information directly into Icicle, which will allow the passing on of FDA alerts directly to Icicle food and beverage RRP users.

USDA, FDA provide APIs for recall data

Recently announced on the FE Website: “USDA’s FSIS Launches New Data Tool: Recall and Public Health Alert API.” The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) launched a new feature on its website that enables software developers to access data on recalls and public health alerts through an application programming interface (API). This is FSIS’ first public API and the organization says it will transform the way the public can benefit from this critical and timely public health information.

The API will act as a bridge, allowing software developers to leverage FSIS recall data to create new value-driven products for consumers or incorporate them into existing digital services and mobile apps. The agency’s recall and public health alert information continues to be publicly available through the FSIS website, X (previously Twitter), FoodSafety.gov, an RSS feed and annual recall data summaries.

Not to be outdone, FDA has also announced APIs for both its coverage areas: food and beverage and pharmaceuticals. Termed openFDA, software developers can incorporate API calls to the FDA site on product and ingredient recalls, and make this information available to their users. You can visit the Food Enforcement Overview page from https://open.fda.gov/apis/food/enforcement/. From there you can find all the info and downloads you need to set up an API for food recalls.

Farmers and Producers Start the Chain

A stumbling block to extending track and trace beyond one-backward and one-forward has been the extra cost to already strapped farmers and producers. What solutions/tools are available to help alleviate the cost and time constraints that producers now experience in entering data? In other words, how do we make their job of entering data easier and at low- or no-cost to them, especially when they are selling to multiple—but unrelated—customers?

“Cost isn’t the only obstacle,” says Burton. “Farmers in many locations, even in North America, don’t necessarily even have electricity or internet connectivity available consistently. That said, one really valuable tool to boost traceability systems and address the standardization problem is the GS1 Global Traceability Standard, which is an internationally recognized protocol for barcoding that is interoperable between different industries, companies, technologies, etc.

“The great thing about GS1 barcodes is that they are very affordable and practical to implement, as are the scanners and label printers necessary to use them,” adds Burton. “With them, you can create a seamless flow of information that can be passed onto your carriers, customers, etc., as well as pulled from your own suppliers if they use the GS1 system, too (regardless of what other technologies they employ). That data flow doesn’t have to be entered manually or involve complicated operations—just simple scanners that are already useful for inventory management and generally improve logistics workflows, eliminate human errors and boost efficiency. While these systems have been broadly adopted by multinational corporations over recent decades, small and mid-sized companies have been slower to adopt them,” says Burton.

GS1’s Role in Track and Trace

GS1 Standards such as Global Trade Item Numbers (GTINs) and Global Location Numbers (GLNs) for identification of products and locations, respectively, are critical to effectively tracking and tracing produce. Electronic Product Code Information Services (EPCIS), a standard for providing event and transactional data about a product’s journey, is becoming important for its ability to not only provide the status of an item (e.g., in transit, temperature, etc.) but also because it supports the FDA’s vision for sharing event data like growing, receiving, transforming, creating and shipping food products electronically. Combined, these three GS1 Standards give the industry a foundation for identifying, capturing, and sharing information about products and support industry’s focus on recording critical tracking events and key data elements to address Final Rule requirements.

— Liz Sertl, Senior Director of Community Engagement, GS1 U.S.

In connecting distributors to farms and producers, the former may need to assume most of the burden in connecting to producers, says Shaw. “This could require special programming and coordination between the fresh produce distributor and other supply chain participants. In order to ensure accurate and efficient passing of grower information, the distributor may need to work with its IT team or a specialized integration vendor to create connections between their ERP or food safety management system and those of their supply chain partners. This could involve developing APIs or using middleware platforms that can translate data between different systems.”

In some cases, there may be standard data exchange protocols in place, such as EDI (Electronic Data Interchange) that can be used to facilitate the transfer of information between different systems, adds Shaw. However, if the data structures are significantly different, there may need to be custom mappings and transformations implemented to ensure that the data is properly formatted and understood by both parties. To avoid potential programming issues, the fresh produce distributor should proactively communicate with its supply chain partners and establish clear data sharing processes and protocols.

“The process must be approachable,” says SafetyChain’s Cohn. “This is where the power of integrations can play a significant role in helping get data to where it needs to go. If, for example, some of the key data elements already exist within another system but need to be communicated in some other way, an API integration can carry that data from one system to the other. Or if the data elements are produced on a case label or pallet label, simply scanning that label and pulling the information into your software is a great way to quickly pick up the data you need without disrupting the normal flow of operations.

“The bottom line is that you need to understand the employees’ and supplier’s specific movements—and how you will tap into the information they have without disrupting their routine or flow,” adds Cohn. End of Part 1