The baking process does not heat inclusions like nuts and chocolate chips enough to properly sanitize them. Processors should seek suppliers that include a kill step for these inclusions. Photo courtesy of Getty Images/Dennis Swanson - Studio 101 West Photography

One of the most significant and powerful statements in all of the United States collection of food regulations may be found in 21 CFR Part 113: “Thermally Processed Low-Acid Foods Packaged in Hermetically Sealed Containers.” The regulation clearly states that processes must be established by a “competent process authority.” The regulation also includes the following definition:

Scheduled process means the process selected by the processor as adequate under the conditions of manufacture for a given product to achieve commercial sterility. This process may be in excess of that necessary to ensure destruction of microorganisms of public health significance, and shall be at least equivalent to the process established by a competent processing authority to achieve commercial sterility.

The regulation, which is now 50 years old, clearly mandates that thermal processes for low-acid foods in hermetically sealed containers—which includes all manner of canned products, aseptic foods in their many packages and other items—must be developed and properly validated by competent process authorities. In addition, these processes must also be submitted to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for review by the agency. For a traditional canned product, the processes will usually include critical factors like process time and temperature for each can size, fill weights, headspace and initial temperature. Failure to adhere to these process parameters can be deadly.

How kill-step validation protects your products and customers

For a new low-acid product, new package type or new processing system, the whole system must be properly validated. In 1981 (Federal Register 46FR 2342, January 9, 1981), the FDA approved the use of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for use as a sterilant for packaging materials. This opened the door for the introduction of a whole raft of equipment suppliers for aseptic processing to look to the U.S. market.

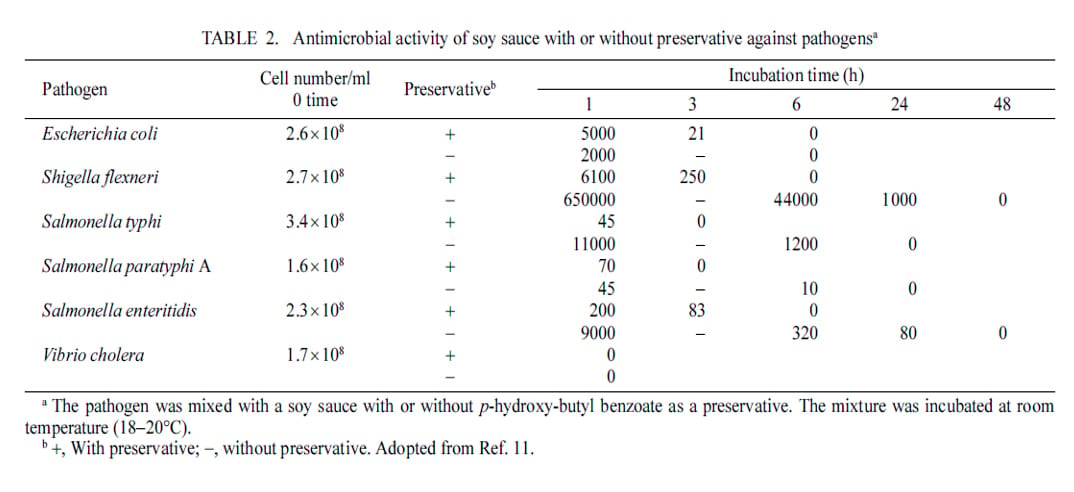

Soy sauce is lethal to pathogens and even spoilage organisms. This table shows how the product is not only bacteriostatic but also bacteriocidal. Kataoka, S. (2005), Functional Effects of Japanese-Style Fermented Soy Sauce (Shoyu) and its Components, J. Bioscience and Bioengineering, Vol. 100:3, p. 227-234

However, although these technologies were being used in Europe, they had to be properly validated for use in the U.S. This meant that microbiologists and processing experts had to work together to establish the necessary processes. And, it entailed determining the surrogates that were to be used in lieu of Clostridium botulinum, plus establishing and properly documenting the procedures to sterilize (and maintain sterility) of the packaging materials, the filling area and the product itself. Researchers at the National Food Processors Association determined that Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus stearothermophilus could be used as surrogates. These organisms were then used to establish the necessary parameters to properly sterilize the packaging materials (paperboard or plastic depending upon the system) and to ensure that the filling area could be sterilized.

Kill step strategy

These examples provide information on how processes are developed for low-acid foods in hermetically sealed containers. These processes constitute a “kill-step,” which is perhaps the best tool that food processors have in their toolbox to ensure consumer safety. What makes this type of food so safe is that the kill step occurs in the final processing step, that is, when the product is in the container. There is very little chance for contamination of the processed product with either a pathogen or a spoilage organism. I say “very little” because contamination does happen. Canned foods will leak and spoil, and there have even been incidents when canned products have suffered post-process contamination with Clostridium botulinum resulting in a botulism outbreak. This occurred back in 1981 with canned salmon from Alaska.

Unfortunately, not all food products available to the public around the world are processed in their final package. The process may include a kill step, but there are handling steps after the process has been delivered that may result in contamination with potential pathogens or spoilage organisms. The two kinds of pathogens of greatest concern when it comes to post-process contamination of Ready-to-Eat (RTE) products are the various strains of salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes. These are also the focus of the environmental monitoring programs that so many companies have adopted to protect their products and customers, and in response to the Preventive Controls for Human Food regulation found in 21 CFR Part 117.

Frozen vegetables bearing on-package validated cooking instructions are considered not-ready-to-eat (NRTE) foods.

There has been a great deal of work in the food industry to develop the necessary validation data to establish kill steps for different products. Kudos to the American Institute of Baking and other processors who have done yeoman’s service in validating many of the traditional baking and frying processes for foods. This work demonstrated that the baked foods that so many have enjoyed for ages are safe with one caveat: the inclusions. Many baked foods include additives such as nuts, whole grains or chocolate chips. The baking processes do not heat these inclusions enough to properly sanitize them. The answer for processors who incorporate inclusions into their baked goods is to be sure that they purchase ingredients in which the supplier’s process includes a kill step.