Fine-Tune

your production with OEE

Applied properly, OEE can improve line efficiencies—but knowing its limitations is important

Overall Equipment Effectiveness (OEE) is a powerful metric for determining production performance. But, does OEE hold its own in being the only KPI you should be using? How should you apply OEE? What data should you use to determine OEE? How useful is it, really?

In this article, I speak with Adrian Pask, vice president business development at Vorne. Founded in 1979, Vorne helps manufacturing companies measure and improve the OEE of their production processes. The company launched a website dedicated to OEE (www.oee.com) in 2002, and in 2005 launched www.leanproduction.com to help people implement Lean Manufacturing processes.

Pask is no stranger to helping companies with OEE. As operations manager with Coca-Cola Enterprises in London, he improved OEE by 16% and reduced changeover time 60% by facilitating operator-identified improvement programs. He led the implementation, verification and process acceptance to deliver the new process in full compliance with The Coca-Cola Quality System (TCCQS), which was subsequently deployed across the European supply chain.

Pask was also consulting director for OptimumFX (part of LineView Solutions), where he provided consulting services and IIoT production monitoring technology to global bottling companies including Coca-Cola Enterprises (CCE), Danone, AB InBev and Doctor Pepper. In that position, he was heavily involved in improving OEE across 14 plants and over 81 lines.

What is OEE?

OEE measures how close you are to perfect production. During planned production time, an OEE score of 100% would mean that you manufactured only good parts, as fast as possible, with no down time.

From Vorne’s OEE website (www.oee.com/calculating-oee.html): “The simplest way to calculate OEE is as the ratio of fully productive time to planned production time. Time is just another way of saying manufacturing only good parts as fast as possible (Ideal Cycle Time) with no Stop Time. Hence the calculation is: OEE = (Good Count × Ideal Cycle Time) / Planned Production Time.”

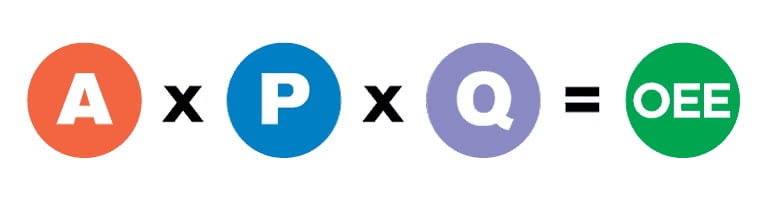

Unfortunately, while this is an entirely valid calculation of OEE, it doesn’t provide information about three loss-related factors: availability, performance and quality. Thus, a more preferred calculation consists of these three factors and can be expressed as OEE = availability × performance × quality, or OEE = A×P×Q.

From the first paragraph in this section, it might seem that if you plan on producing say, 100 perfect candy bars per minute, and you actually make 100 perfect bars per minute, your OEE might be 1.0 or expressed in percent, 100%. Right? Yes, but… Since the OEE score is the product of availability, performance and quality over a sustained run time that you set, real-world results will never equal a perfect 100%. But, do you need a 99% OEE for your process to be efficient and to make money?

Wayne Labs, Senior Technical Editor

Intro video courtesy of Getty Images/Dem10

Adrian Pask,

Vorne VP of business development, previously as Coca-Cola Enterprises operations manager in London, U.K., improved OEE by 16% and reduced changeover time by 60%.

Apply OEE properly to get useful information

So, how useful is OEE? What are its limitations and application—so we can derive the most benefit from it?

Pask says most companies place too much emphasis on results (i.e., looking backward at OEE scores) and too little emphasis on the factors that actually drive results. So then, two questions arise. Is OEE a useful tool in improving manufacturing capability? And, should manufacturers be using something beyond just OEE to improve their process? In a previous Food Engineering article, Pask also described the “IDA equation,” which is another tool derived from OEE.

“Your use of the word ‘tool’ in the question is important. Like any tool, OEE needs to be applied correctly to the right task, to create the outcome that you want,” says Pask. If the objective is to optimize the manufacturing efficiency of a machine-constrained process, then OEE is a tried-and-tested best practice tool for identifying and categorizing the causes of lost production.

Some companies are installing overhead status boards on new production lines, which can be helpful if they provide useful information besides OEE—for example, downtime losses, changeover losses, speed loss and defect count. Image courtesy of Imagemakers Inc.

OEE is really a measure of time and it notably doesn’t track labor efficiency, yield, adherence to customer orders, safety, or any other metrics that are not purely machine and time based, says Pask. “I always recommend that manufacturers think of OEE as ‘another’ tool in their productivity tool box, a tool with the specific intent of identifying lost production time. IDA is a concept that helps us to directly connect OEE data with actions to improve productivity, and I’m looking forward to getting back to it later!”

OEE should be used to compare apples with apples

When manufacturers use OEE to compare dissimilar processes or lines with dissimilar production schedules, it no longer makes sense to compare OEE scores because they’re not comparing apples to apples. Is this really a common practice and how can manufacturers avoid making this mistake? Should a line technically only be compared to itself in terms of OEE? Carrying this concept one step further: If a manufacturer has two identical lines side-by-side, but different human operators, then is it OK to compare these two lines with OEE?

“Unfortunately, comparing OEE scores across processes is a common and extremely tempting practice,” says Pask. “I absolutely understand the desire to compare the scores for ‘how our processes are performing,’ and on an enterprise dashboard OEE does provide a sense for how multiple processes are running. However, we need to understand that comparing or aggregating OEE like this can lead you to misleading conclusions.”

For example, imagine a manufacturer has two identical processes, utilized equally for a week. One process is scheduled to produce five SKUs, so the manufacturer might hypothetically expect a good OEE to be 85%-90%. On the second process, the manufacturer makes 35 SKUs, so it might hypothetically expect a good OEE to be 50%-55%. At the end of the week, the actual OEE scores are 70% for process 1, and 48% for process 2. Pask asks: “Which process had the better week?” (Hint: it’s not the one with the higher score!)

“We advise that people only compare OEE scores for one process over time, to see how the productivity of that process has changed over time,” says Pask.

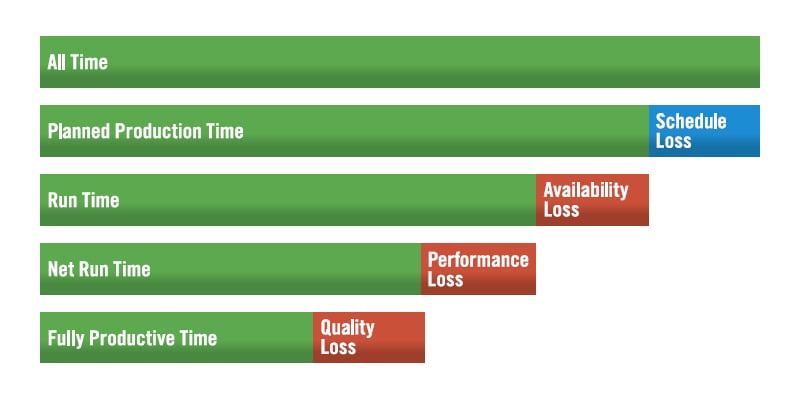

OEE measures the percentage of planned production time that is truly productive (the ratio of Fully Productive Time to Planned Production Time). Image courtesy of www.vorne.com

“To your example of the identical lines with different operators, if the operators are the only variable maybe OEE can provide some interesting insight; but I’d be more tempted to focus on other metrics that more directly measure the effectiveness of the people,” says Pask. For example, mean time between failure (MTBF) and mean time to repair (MTTR) could be more useful.

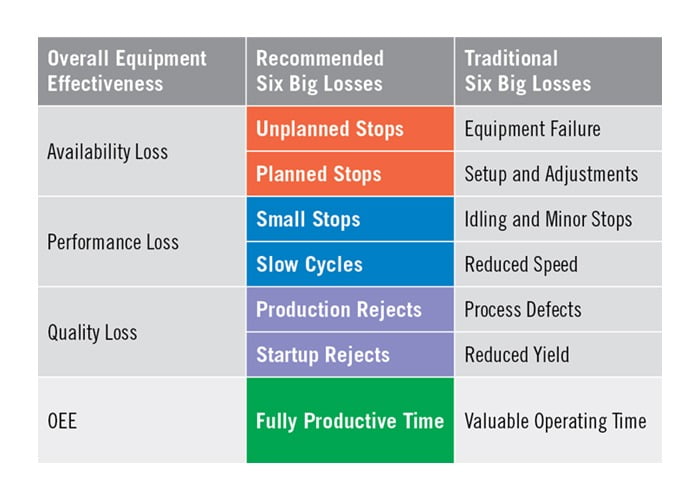

OEE is calculated by multiplying the three OEE factors: Availability, Performance and Quality. Image courtesy of www.oee.com

Other OEE misapplications

There are other mistakes processors make in applying OEE, says Pask. The two biggest mistakes are:

1. Boosting the score—That is, manufacturers hide their causes of lost time to boost the OEE number. There are several ways to artificially boost the OEE score, says Pask. The two biggest and most common mistakes are:

• Soft Ideal Cycle Time: Using an Ideal Cycle Time that’s either based off a ‘budget/standard,’ or has been reduced to account for a running condition (such as insufficient operators or material problems) hides the real capability of the process.

• Hiding Lost Time: Converting legitimate causes of machine stops into not scheduled time, to exclude them from the OEE (such as no operator, no material).

2. No Action—Measuring OEE should not be a goal. Using the tool analogy, picking up a hammer is not the same as using it to build a house. “If you’re measuring OEE you’ve ‘picked up the hammer’ but OEE has no intrinsic value until you start using the losses captured identified by the OEE calculation to improve productivity,” says Pask. “I’m fond of saying ‘Data without action is waste!’”

Next, what are best practices for applying OEE properly? “First, make the measurement of loss absolutely brutal,” says Pask. “By ‘brutal,’ I mean that when we first measure OEE it should include every possible cause of lost production time. My goal when implementing OEE is to create the lowest possible initial OEE score, by including as many losses as possible. This provides the best baseline from which you can subsequently improve.

“Second, actively consider and identify when and how you will use OEE in your decision-making processes. For example, how will you use your OEE-related data in a shift handover, in a daily production meeting, to set improvement goals, to identify maintenance activities. Going back to the ‘tool’ analogy: I’m advocating that you actively consider when and how you will use your OEE tool to build better productivity.”

Is OEE on its own a good metric?

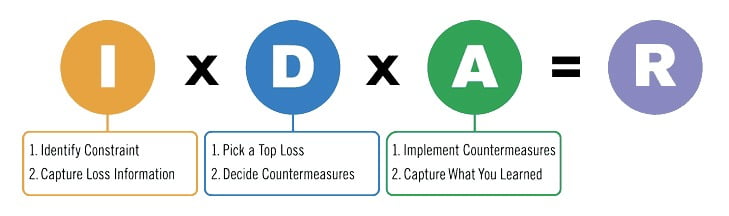

In a SensrTrx blog post, Marketing Manager Lindsey Andrews states that OEE by itself is not a good metric, but its components—availability, quality and performance—are. I asked Pask if this is where the results-oriented equation he mentioned in my 2016 FE article comes into play. That equation is R (results) = I (Information) × D (Decisions) × A (Action). I wanted to know how R = I×D×A works, and its benefits when compared to a raw OEE score?

“Yes, I agree that the OEE percentage score has limited intrinsic value,” says Pask. “I only care how the score has changed over time. Knowing the score doesn’t guide your improvement actions; for this you need to know (and act on) your losses.”

IDA (Information, Decision, Action) is a simple and highly effective process for improving productivity using information. Image courtesy of www.oee.com

IDA is a framework for thinking about the relationship between Information and results. Information (I) is the foundation for effective decision making, and should have various definable and auditable characteristics (e.g. accuracy, identifying losses).

Information is leveraged in meetings to make Decisions (D). These meetings should also have various definable and auditable characteristics (e.g. scheduled, proactive).

“Based on the Information and Decisions, we take Action (A),” says Pask. “Again, we should define what constitutes ‘good’ quality actions so that we can audit the effectiveness of our actions (e.g. timely, escalated when needed).

“By defining our desired characteristics for each component of IDA, we can audit how effectively a team is managing its process to improve their Results,” says Pask. “The parallel here is that just as how OEE is comprised of your Availability, Performance and Quality—and your OEE score is heavily affected by your weakest component—IDA works the same. If you have a great decision-making process, and really effective action-completion, but poor quality information then you’re unlikely to be improving productivity effectively.”

OEE doesn’t and shouldn’t be a standalone score with no connection to other metrics, says Pask. The losses identified by OEE provide data points that can be used for any equipment-based production improvement initiative and as OEE was developed as part of TPM, it is especially well-connected to maintenance activities. Six Sigma, as a tool that is aligned to improving the defect rate of parts, likely benefits the least from OEE information.

Broadcasting OEE for everyone to see

On a more practical note, I’ve been to plants where large video screens display scores (often number of good products vs. rejects), up times and/or down times and sometimes OEE scores. I asked Pask for his advice to processors who would like to use these stat boards in plant areas?

“Simply: Focus on your losses,” says Pask. “The OEE percentage doesn’t tell us how to improve. Availability, Performance, and Quality are all abstract percentages. I recommend tracking two things on the factory floor:

1. Display efficiency: The extent to which the team is on track to hit their shift production target. Ideally this is like a ‘pace clock,’ so that if a process starts to fall behind their target we can prioritize focus to get them back on track.