Heat Pumps

The threat of finite natural resources can be managed by switching to heat pumps—a move that will pay for itself in resulting energy-cost reductions.

are the Past, Present and Future

Industrial Heat Pumps

For industrial heating, facilities generally have two options: opt for gas-fired furnaces, boilers and hot-water heaters, or embrace heat pumps. One of these options carries significantly more risk than the other.

Even at low-source temperatures, heat pumps are always more efficient than gas-fired devices as they move heat rather than create it. In many industrial applications, heat pumps are at least three times as efficient for heating purposes, and they also negate the longer-term risk of dwindling fossil fuel supplies and consequential price increases.

Alternative solutions like using hydrogen as a heat source are not yet market ready and they aren’t likely to ever be cost competitive—further strengthening the business case for tried-and-tested industrial heat pump technologies that boast favorable return-on-investment numbers and impressive 30+ year system lifespans.

Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash

by Wayne Borrowman

Wayne Borrowman is the director of research and development at CIMCO. He has more than 35 years’ experience in industrial thermal engineering, having been involved in more than 1,000 projects. He is the also involved in various industry safety and design committees as an industry expert.

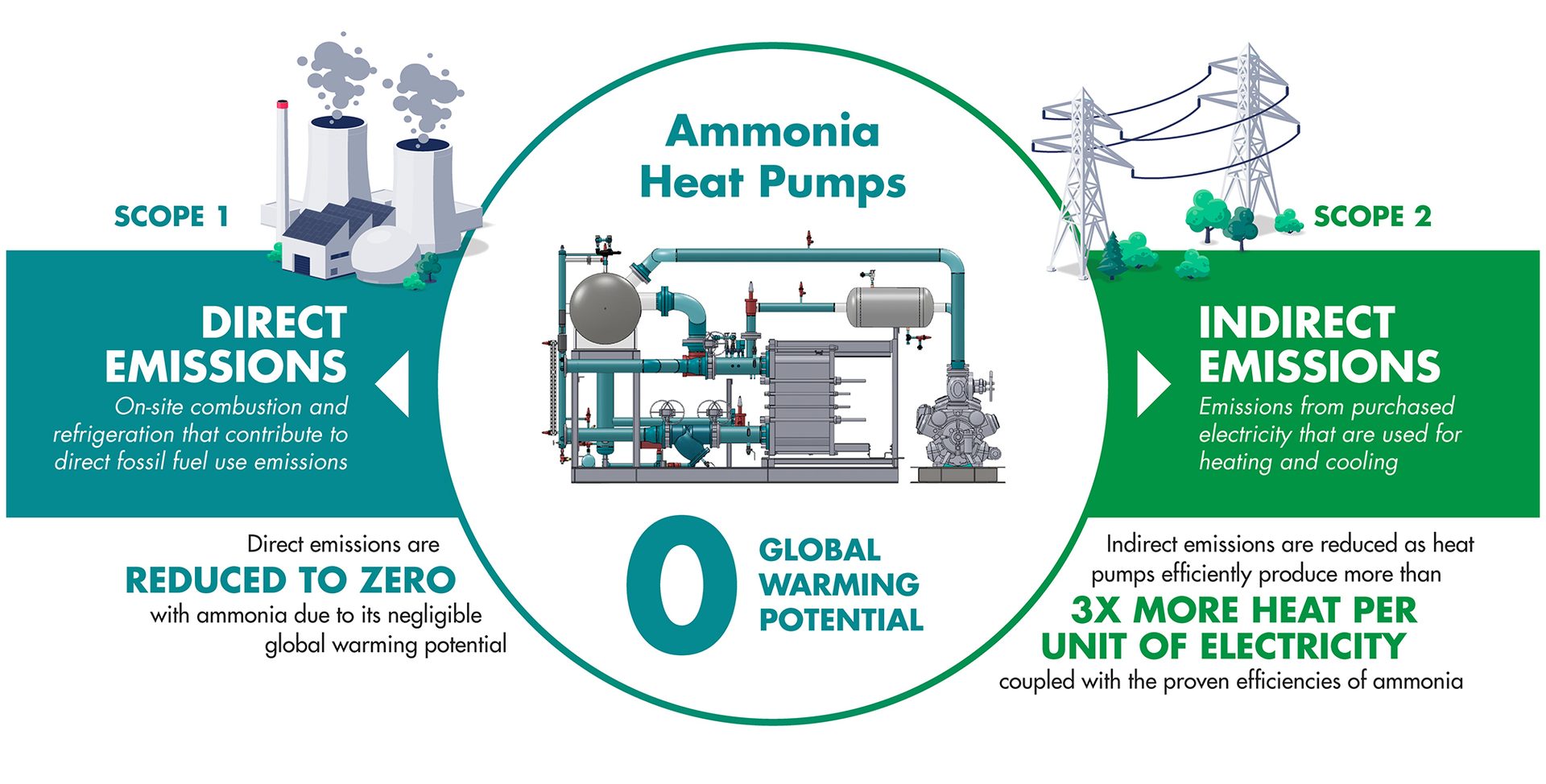

Not all heat pumps are the same, though, and the availability, price, longevity and environmental impact of refrigerants also need to be weighed before selecting an industrial heat pump. Natural refrigerants (not to be confused with natural gas) like ammonia and CO2, have zero global warming potential (GWP) and proven efficiencies in industrial applications, reducing both scope 1 and 2 emissions. Meanwhile, even the new lower-GWP fluorinated gases (f-gases) often have GWPs hundreds of times greater than that of CO2 and face an uncertain future as global policies double down on phasedowns, creating insecurity around availability and costs.

What is the real cost of not making the switch to heat pumps?

Heat Pumps are Nothing New

Despite often-confusing claims that heat pump technology is complicated and new, these systems are no more complex than any other refrigeration circuit. Heat pumps were invented in 1856 and can be found in virtually all sectors and geographical regions.

During the 1960s in North America, recovering and reusing heat from industrial refrigeration systems was considered “convenient” but already widespread. That mentality changed in the 2000s, when forward-thinking companies like CIMCO began providing solutions that recover up to 100% of the rejected heat in economically viable industrial projects.

As energy costs continued to rise, heating became even more important—no longer just a byproduct of refrigeration. That’s when heat pumps really started to shine, shifting the focus to heating efficiency. Today, equipment exists that combines both heat recovery and heat pump technologies for optimal efficiency.

Fossil Fuel Resources will Eventually Run Out

Fossil fuel formed millions of years ago, and although we have only been using it for 200 years, we are consuming what took millions of years to form in the geological blink of an eye. Although new reserves are being discovered, these will become harder and harder to find and eventually will not be able to meet expected energy usage needs.

Based on data collected by the MET Group, fossil fuel resources will run out quickly: oil within 51 years, coal in 114 years and 53 years for natural gas. This is based on data from 2015 and other sources quoted by the MET Group estimate that we will run out of fossil fuels much quicker, with usable oil deposits gone as soon as 2052.

Even if we didn’t care about the detrimental effect fossil fuels have on the environment, there simply will not be any more natural gas to use in the future.

Yet hydrocarbons (which is what fossil fuels effectively are) are being wasted by simply burning them instead of saving them for deriving vital products that will be very difficult to make in the future. It makes sense to use heat pumps for heating applications and save this limited resource rather than squander it.

Comparing fossil-fuel heating to heat-pump heating. Image courtesy of CIMCO

Natural Refrigerant Heat Pumps Make Sense

The vast majority of large industrial refrigeration installations already use natural refrigerants, even in North America, making it easy to imagine a future of using 100% natural refrigerant heat pumps in the industrial sector. Natural refrigerants will remain economical as they cannot be patented and their costs have remained stable over the decades. Plus, they will never be phased down or out.

In North America, one would struggle to find any refrigerated product in a grocery store that has not been cooled by an ammonia refrigeration system somewhere in its cold chain—from the food processor to the refrigerated distribution warehouse. The Global Cold Chain Alliance estimates that more than 90% of its North American refrigerated warehouses already using either ammonia or CO2 refrigerant.

Using natural refrigerants instead of f-gases creates peace of mind for customers, eliminating the risk of looming refrigerant phasedowns. It also significantly reduces emissions—both scope 1 and 2 emissions.

Taking it a step further and integrating a heat pump function into these refrigeration systems result in higher efficiencies compared to separate standalone heat pump systems and makes sense in this sector where ammonia safety regulations and protocols are already well developed for the refrigeration system.

Using natural refrigerants instead of f-gases creates peace of mind for customers, eliminating the risk of looming refrigerant phasedowns. It also significantly reduces emissions—both scope 1 and 2 emissions.

Scope 1 emissions, which are considered direct emissions, are reduced to zero with ammonia thanks to its negligible GWP impact, while scope 2 emissions (from energy use) are also cut thanks to ammonia’s proven efficiencies (additional to the efficiency gains of switching to a heat pump), especially in industrial applications. Making the switch streamlines any facility’s decarbonization journey, also cutting carbon tax costs.

Using natural refrigerants versus other options has both direct and indirect emissions benefits. Image courtesy of CIMCO

Risk of Not Switching Over

In the future, when fewer users consume natural gas, those who remain will also end up paying more to maintain that distribution network. It will only become more difficult and more expensive to continue running natural gas equipment in the future, so why not make the jump earlier? Especially considering that switching is inevitable.

Industrial heat pumps typically have a coefficient of performance (COP) of 3 or higher, meaning that for each unit of energy supplied, three units of energy are output. Applications that scavenge waste heat from refrigeration systems and increase it to a higher temperature typically have a COP of 5 to 7. Some heat pump applications can have a COP as high as 10. When you do the math, on industrial applications, the return on investment is often as low as five years when compared to using natural gas combustion (according to the U.S. Department of Energy’s calculation using 2022 utility rates).

Assuming a payback of five years, if you put in the heat pump system today, the system will be paid for within five years and you will enjoy a competitive advantage over competitors who did not invest earlier in this inevitable switch.

Natural refrigerant industrial heat pumps can be designed for a life expectancy beyond 30 years; typically every part of them is serviceable or replaceable—they are not throwaway technology. It makes sense to put in a futureproof technology instead of one that will have to be replaced before the end of its usable lifespan due to resource shortages or costs.

In the end, switching over to heat pumps, ideally natural refrigerant heat pumps, for industrial applications is no longer a question of if, but when. FE