march 2023

Sustainability

‘LEED Equivalent’

The Myth of

A name on a plaque is more than symbolic, it means accountability mechanisms on building projects are ensured.

BY Daniel Overbey, AIA, NCARB, LEED Fellow

Photo courtesy of Getty Images / AlexLMX

It goes my many names:

…LEED-like.

…Built to LEED standards.

…LEED equivalent.

I will offer one more: a ruse.

Full disclosure, I am writing to you as a LEED Fellow. I have helped lead projects teams that have accounted for millions of LEED certified square footage. Like many of us, the U.S. Green Building Council’s (USGC) LEED rating system has benefitted me and my business. However, it has also transformed the building sector toward greater sustainability.

As imperfect of a system as LEED may be, it continues to improve, and the building design and construction industry has never before seen a tool that has been more effective in shifting the building sector toward better, healthier, more responsible outcomes. LEED buildings and communities exist in more than 180 countries and equate to around 2.2 million square feet being certified daily. Clearly, the international market knows how to deliver high-performance, low-carbon, environmentally responsible buildings. Perhaps we don’t need LEED to guide us how to create and manage green buildings and communities.

But the caution I raise against so-called “LEED Equivalent” buildings has nothing to do with the LEED rating system or the LEED brand itself. Rather, it has everything to do with ensuring accountability mechanisms on building projects in the face of the limited resource capitals of time and money.

The proposition of LEED Equivalent seems innocent enough—and in simplistic terms, it stands to reason as a fiscally responsible notion: Why spend limited budgetary funds on a LEED project registration and certification review if a team has the know-how and the pertinent information is embedded in the project’s contract documents? Put in terms we might all be more familiar with, “Why spend money just to put a plaque on the wall?”

This notion of designing and constructing “to LEED standards” would suggest that everything short of paying for the LEED certification process would be accomplished on the job, including implementation of an integrative design team, high-performance systems, specification requirements, energy modeling, commissioning of the mechanical systems, due diligence and oversight during procurement, documented records of plan execution with regard to construction activity pollution prevention on the site and inside the structure, and so on—less there may be corners cut and the project would not, in fact, realize a “LEED Equivalent” standard.

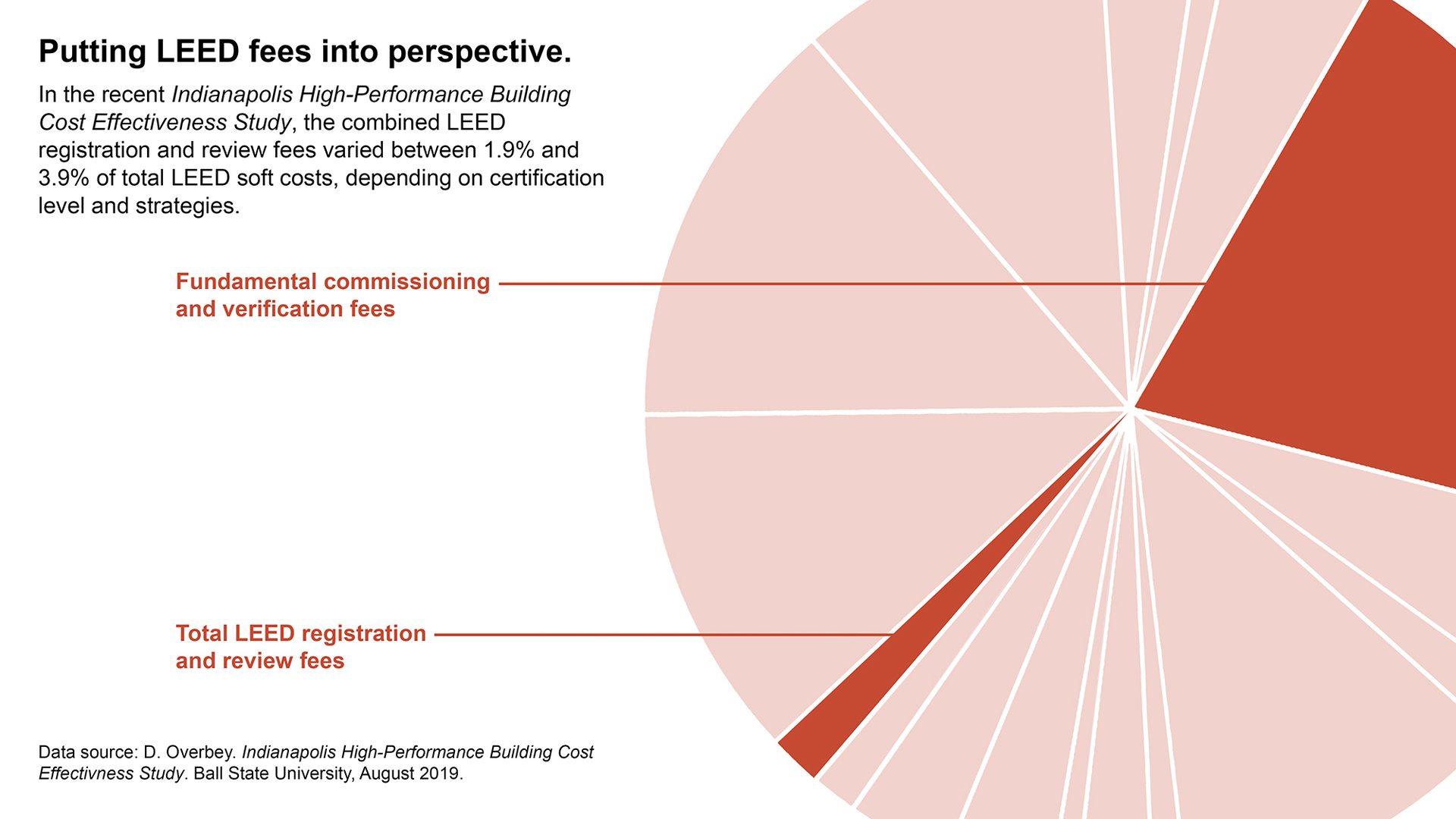

In a recent study by Ball State University in collaboration with a team of building sector industry partners, namely Browning Day, Turner Construction and Applied Engineering Services (again, full disclosure, I served as the principal investigator for the study, and I am associated with both Ball State University and Browning Day), it was determined that for a standalone suburban office building in the U.S. Midwest, a team might expect the LEED registration and review to constitute around 2-4% of the total project soft costs to otherwise accomplish a “certifiable” LEED building (Fig. 1).

Daniel Overbey, AIA, NCARB, LEED Fellow, LEED AP (BD+C, ID+C, O+M), WELL AP, EcoDistricts AP is an assistant professor of architecture at Ball State University’s R. Wayne Estopinal College of Architecture and Planning and is an associate principal and director of sustainability for Browning Day in Indianapolis.

Figure 1: Putting LEED fees into perspective.

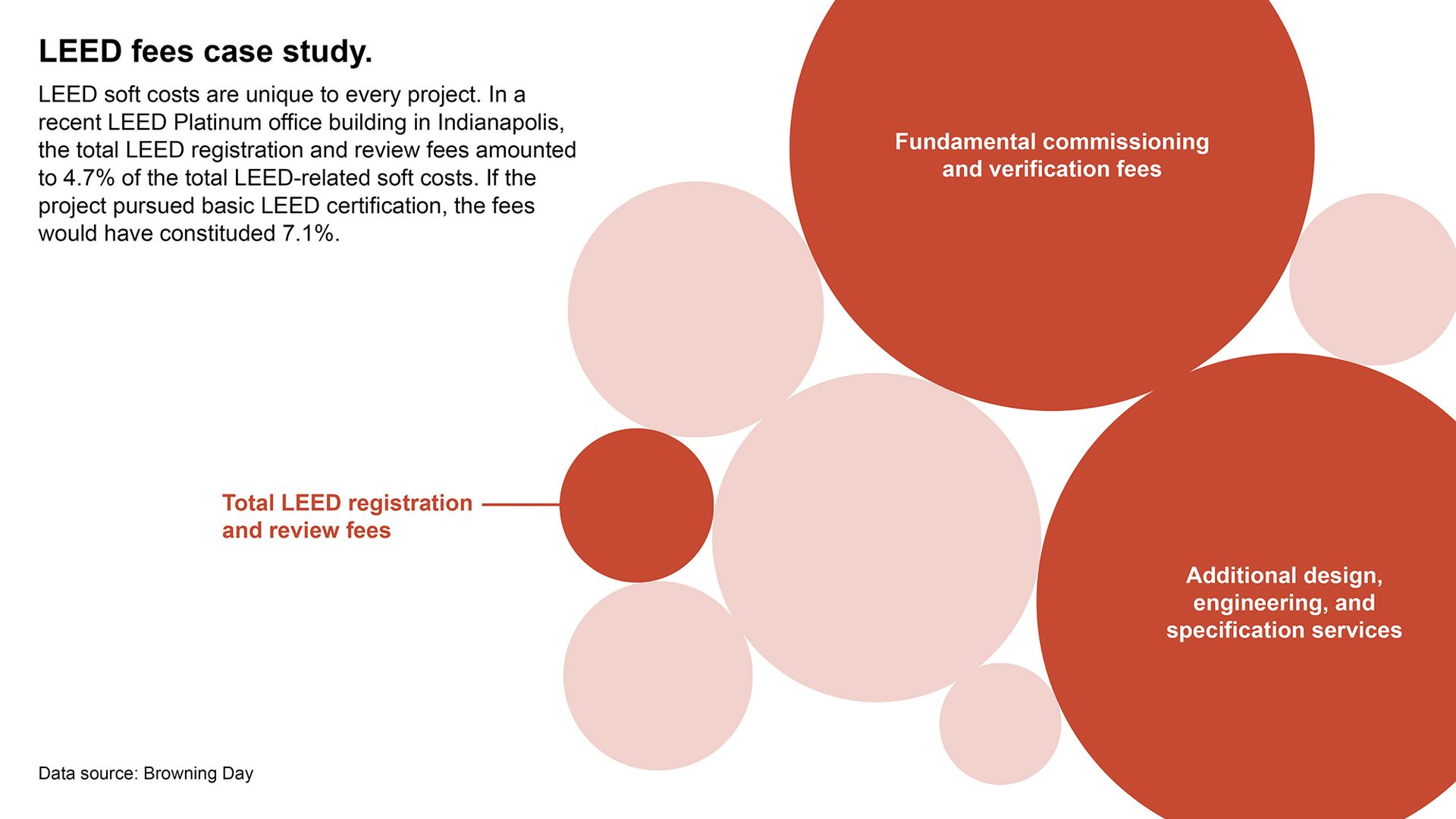

My work in managing LEED projects has reinforced the findings. For instance, I compared the figures from the study to a 160,000-sq.-ft. standalone corporate office building in Indianapolis that my firm recently completed that achieved LEED Platinum certification. The story was similar: Our total LEED fees accounted for 4.7% of the project’s total LEED-related soft costs. If we only pursued basic LEED certification and opted out of a few additional services including acoustic and daylighting optimization, the proportion rose to 7.1% (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: LEED fees in a case study.

On a risk-adjusted basis, it makes little economic sense to pursue “LEED Equivalent” as the minuscule LEED registration and review fees fund the third-party certification review managed by Green Business Certification Inc. (GBCI). What LEED Equivalent calls for (in theory) is that a project team expends time and money on over 90% (perhaps as high as 98%) of the LEED certification effort but declines to spend money on the third-party quality assurance process that ensures the energy modeling was complete and correct, the commissioning was properly executed, and that what was designed and specified was actually executed in the field.

Stated differently, LEED Equivalent means that a project team will spend over 90% of the money necessary to create a green building but will decline to spend a fraction more to capture the reputational capital of the LEED brand and ensure that the design and construction team delivers what the owner thinks they are paying for in terms of the green building qualities of the project. FE

MARCH 2023