Sharing information about cyberattacks can help strengthen the entire industry

What food processors won’t talk about

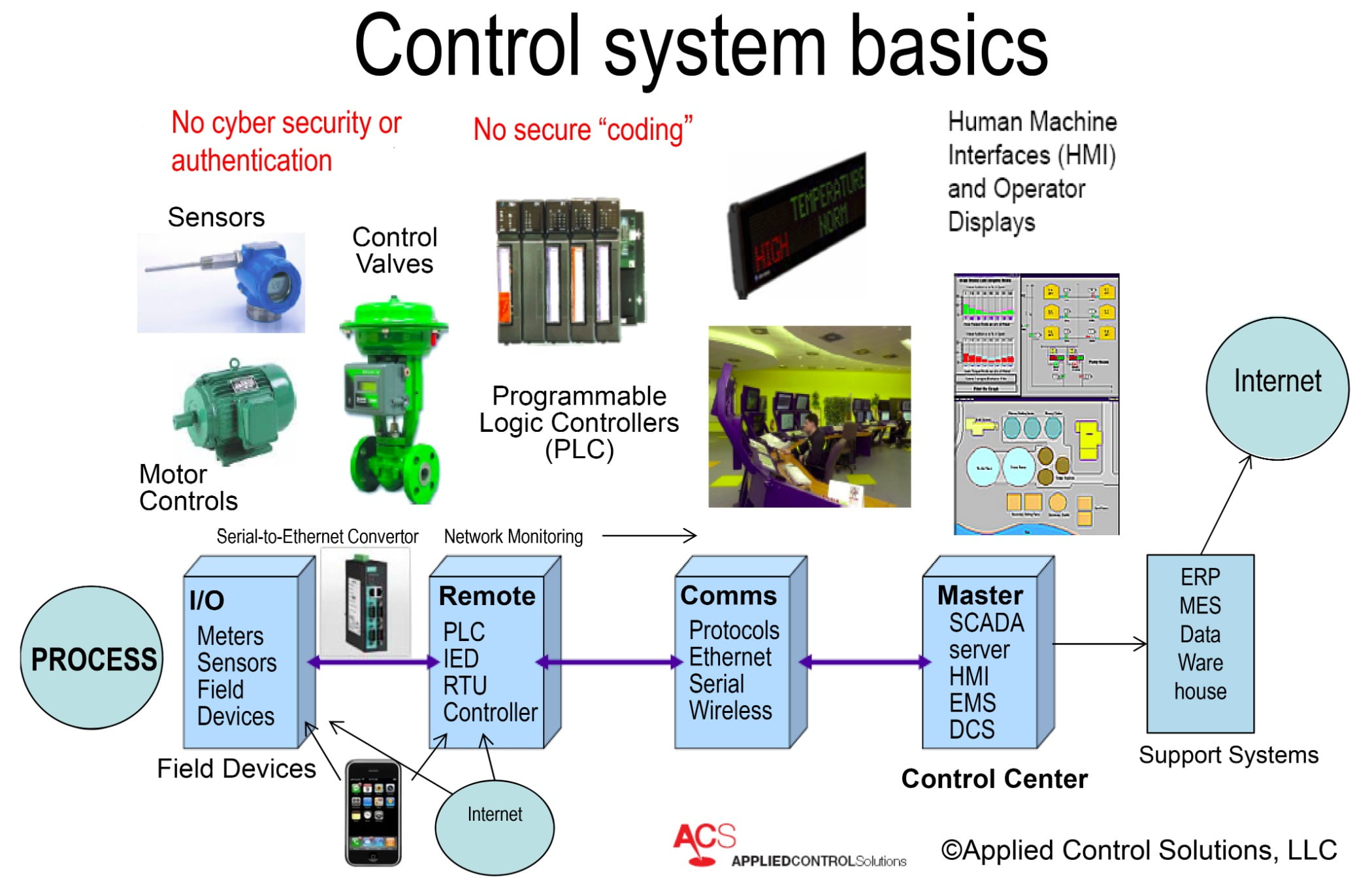

With today’s remote monitoring through the internet of sensors, controllers and machines, control networks can be compromised without even connecting through the IT network. Photo courtesy of Joe Weiss, Applied Control Solutions LLC

An issue food processors won’t talk about openly is whether they’ve been the victim of a cyberattack. This is unfortunate for the industry as a whole—because the more the topic is discussed, the more processors can be made aware of cyberattack vectors and learn how to prevent future unintentional cyber incidents and malicious cyberattacks.

Unfortunately, most of the discussion that takes place revolves around high-visibility ransomware attacks on IT systems. However, underlying is something far more insidious, dangerous and pernicious—the cyberattack of process control systems without the food/beverage manufacturer’s knowledge.

In most cases, process control system cyberattacks, when executed by sophisticated hackers are virtually undetectable, unlike the Feb. 4, 2021, cyberattack carried out via remote desktop protocol of the Oldsmar Water Authority in Florida. Even so, that event should be a wakeup call, especially as it is similar to control system cyber incidents that have occurred in the food industry.

Process control system cyberattacks are very difficult to detect for several reasons and are often attributed to some sort of unaccountable “process upset.” Unfortunately, these process upsets have been known not only to cause financial damage by out-of-specification product, but also make people sick with tainted food, which could be, for example, the result of a control system process gone awry or the incorrect addition of additives or chemicals. These types of potentially dangerous incidents could be caused by unintentional actions or by malicious intent.

Although FDA’s Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) includes a rule that seeks to mitigate acts of intentional food adulteration, there was nothing written into the law to require control systems be assessed for vulnerability to a cyber attacker. Therefore, it is still up to the food or beverage processor to make sure a product has not been the victim of tampering—just as it’s incumbent upon the processor to verify that imports and ingredients are safe and unadulterated. This is analogous to supply chain integrity in other industries.

I spoke with Joe Weiss, PE, CISM, CRISC, ISA Fellow, IEEE senior member and managing director ISA99, who also has his own consulting company, Applied Control Solutions LLC, and is a world-renowned expert on control system cybersecurity. Weiss is an industry expert on control systems and electronic security of control systems, with more than 40 years of experience in the critical energy industry. He has spent more than 14 years at the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), the first five years managing the Nuclear Instrumentation and Diagnostics Program.

Joe Weiss, Advanced Control Solutions LLC

FE: Joe, we know hackers can enter process control systems from IT, but are there also entry points closer to the process control system itself? How should food/beverage processors monitor and protect these points of entry?

Joe Weiss: It is important for people to understand what control systems are and where they can be cyber vulnerable. Instrumentation (sensors, analyzers, etc.) and control systems (actuators, valves, motors, etc.) measure and control all physical processes. This includes manufacturing, energy, power, water/wastewater, pipelines, transportation, medical, defense, etc. Control systems consist of process sensors connected to controllers, actuators and HMIs (effectively, the control system network). The sensors and actuators operate almost exclusively in near-real-time (microseconds to milliseconds), whereas the Human Machine Interface or HMI (operator displays) provides operator information on the order of seconds to minutes. The sensors and actuators can operate, and in most cases were designed to function, without the Internet Protocol (IP) network. The figure shown provides a representation of the equipment and information flows in a typical process system. There is no cyber security or authentication in sensors and actuators.

Specifically, control systems and control system devices may have inherent cyber vulnerabilities such as hardware backdoors to calibrate transmitters or hardcoded default passwords in some vendors’ programmable logic controllers (PLCs) that cannot be changed. It is important to recognize that “air gaps” between the IT and OT (operational technology) networks do not exist and that monitoring the IT network alone is not sufficient. The organization needs to assure control system vendor recommendations are being followed, including that patches have been implemented on a timely basis and remote access secured.

There are network monitoring tools available that can provide visibility into the OT network and provide as-installed device logging. Access to devices and device network should only be by those with pre-approved authorization, and all changes should be logged. Performing diagnostics and random “tests” of the system, “parasitic” or unplanned entry—potentially malicious acts—attempting to access the control system could be valuable.

Detecting, interdicting and preventing these actions in real time is the key, but it’s also the biggest challenge. It is often difficult to distinguish between false positives and false negatives. That is, are you seeing “blips” that could be indicative of a hack or just a momentary system event? Either case could be important, but for different reasons—security versus equipment operability. The false negatives are hidden cyber threats such as “Trojans” that are passively awaiting an attacker to initiate. Understanding these complex issues requires network expertise and detailed understanding of the control systems used in the food manufacturing process.

FE: We’ve seen that the food industry is a pretty popular target for hackers, according to a recent Claroty survey. Do you have any idea roughly what percentage of food industry cyberattacks are at the control system level?

Weiss: IT cyberattacks such as ransomware are becoming more prevalent and are readily identifiable as being cyberattacks. However, there are minimal control system forensics at the control system device (e.g., process sensors, actuators, variable frequency drives, etc.) and device network layer (e.g., HART, Profibus, etc.) There is also a lack of training for the manufacturing engineers to identify potential cyber-related incidents. There is also a reticence to identify control system/operational incidents as being cyber-related because of the optics and reporting requirements associated with a cyber incident.

Consequently, there are few identified control system cyber cases in food or other industrial and manufacturing industries. I have identified more than 30 control system cyber incidents in the food and beverage industries, which include both malicious and unintentional incidents. These incidents ranged from shutting down facilities, impacting factory-floor networks and damaging plant equipment, to adulterating food leading to consumers getting sick.

FE: How can food processors know their process control system has been hacked, and is there any effective way of monitoring whether their system has been or is being hacked?

Weiss: There are OT network monitoring technologies that can help provide observability into the OT networks. A comprehensive program would combine the network monitoring with understanding of what’s normal/expected within the operating environment.

Through rigorous (often already in place) finished product quality control measures, anything that is found to be out of specification could be an indicator of something amiss with the control systems. I tend to refer to this as a “sanity check.” That is, does what we’re seeing in finished product align with what we would have expected to see?

For example, have conditions occurred that should have initiated alarms, but didn’t—or were alarms initiated that ostensibly shouldn’t? Were there system configurations set that didn’t make sense or were not authorized (this can be identified through the OT network monitoring)? The sanity check approach requires training and coordination between IT, OT and plant engineers. This approach can help improve reliability and productivity and also improve working relationships between diverse organizations that haven’t always effectively worked together. This approach applies beyond the food industry and should be considered for all critical infrastructure operations that rely on process control systems.

“Industry needs to recognize that sharing control system cyber incident information is not a competitive issue, but can help to prevent the next “event” from occurring that could affect multiple food processors.” — Joe Weiss, managing partner, Applied Control Solutions LLC

What can we do in the future to increase awareness of process control system hacks? Why are we where we are today?

Weiss: In order to increase awareness of potential process control system exploits, there is a need to share information from control system cyber incidents across all critical infrastructure (CI) industries. Because the food and agriculture sector “as a whole” does not have an information sharing and analysis center (ISAC) as many/most other CI sectors do, it makes it harder for food and beverage manufacturers to share information in a trusted environment.

Industry needs to recognize that sharing control system cyber incident information is not a competitive issue, but can help to prevent the next “event” from occurring that could affect multiple food processors. This is a hurdle that needs to be broken down, so that all manufacturers can benefit and learn from others’ incidents. This can help to prevent the next event from being bigger and potentially more disruptive in scope.

The food industry uses the same equipment from the same vendors as other industries. Consequently, a control system cyber incident affecting common equipment can affect multiple industries including food and agriculture producers. Conversely, absent more thorough awareness and practical implementation of mitigations to stem the attacks on process control systems, the food (and other) industries are doomed to repeat the events, like the Oldsmar water system breach.

CISA (Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency) and control system vendors provide notifications of OT network and control system device vulnerabilities. However, the same can’t be said for sharing information about control system cyber incidents. February 3, I wrote a blog about the lack of sharing control system cyber incidents. All industries need to share information about control system cyber incidents and associated lessons learned. March 23, I had a call with representatives from InfraGard’s National Sector Leadership to discuss the control system information sharing issues. I am looking forward to help to those with the ability to make changes to more fully understand the enormity of the problem and what can be done.

For more information, contact Joe Weiss at joe.weiss@realtimeacs.com. FE